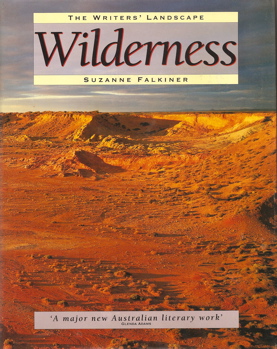

THE WRITER’S LANDSCAPE: Wilderness

THE WRITER’S LANDSCAPE: Wilderness

Simon & Schuster, Australia

1992

ISBN: 073180144X

Landscape, Literary history

Available from:www.abebooks.com

Photographs by WILDLIGHT

‘But the dweller in the wilderness …becomes familiar with the beauty of loneliness…learns the language of the barren and the uncouth…and the Poet of our desolation begins to comprehend why free Esau loved his heritage of desert sand, better than all the bountiful richness of Egypt.’

—Marcus Clarke, 1867 [Preface to Adam Lindsay Gordon’s

Sea Spray and Smoke Drift]

What they said:

In this superbly researched assessment of our literature and its landscape, Suzanne Falkiner takes us on an absorbing journey into the ‘fictional megacontinent’ of the Australian imagination. Drawing us into the visions of Australian writers past and present, she invites us to share her insights and responses to the mystery of this perplexing continent. The Writers’ Landscape is Suzanne Falkiner’s unique contribution to the emotional mapping of the Australian experience.

A major new Australian literary work

—Glenda Adams

Back in the 1940, writers were preoccupied with time, real and imaginary. In the nineties we are concerned above all with reading space within the Australia we have imaginatively created. Suzanne Falkiner has mapped this space for us in fascinating detail: her appetite for textual Australia is boundless.

—Chris Wallace-Crabbe

‘Suzanne Falkiner’s Wilderness is a garden of delights. This is one of the most imaginative, innovative and useful books on Australian literary culture to emerge for some time.

—David Tacey Australian Book Review no.147

December-January 1992-1993

[Settlement] is stylish book, rich with illustration…a unique way to an understanding of Australia’s capital cities-historically, culturally and geographically…it offers an alternative approach to our history in terms of landscape and literature.

—Julie Lewis Australian Book Review no.147

December-January 1992-1993

‘This book, or books, is, or are, long overdue. Australian writers and critics have spent a great deal of time analysing the effect of the landscape on the Australian psyche, but there are few works that have focused specifically on the sense of place in our imagination.’

—Laurie Clancy The Australian ‘Weekend Review’

14-15 November 1992

‘Inspired…The underlying intention [of the two volumes] is to describe the affect of this great slumbering beast on the conscious and the unconscious of the writer…Falkiner’s work embraces and celebrates what we have been, but more importantly what we might hope to become. The Writer’s Landscape is essential for anyone interested I our history, literary or otherwise.’

—Helen Elliot The West Australian

31 October 1992

‘Two new books capture the voices of a nation’

—Christian Science Monitor Boston

20 January 1993

Read an extract...

‘HAVE YOU walked upon the bottom of the sea, Mr Pringle?’ the German asked. ‘Eh?’ said Mr Pringle. ‘No.’

His eyes, however, had seen into unaccustomed depths.

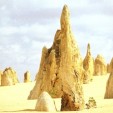

‘I have not,’ said Voss. ‘Except in dreams, of course. That is why I am fascinated by the prospect before me. Even if the future of great areas of sand is a purely metaphysical one.’

Then he threw up a little pebble, which had been changing colour in his hand, turning from pale lavender to purple, and caught it before it reached the sun.

—Patrick White Voss 1957

(Wilderness page 100)

BLOUNT STIRRED HIMSELF and said: ‘Why are we here? Nothing floats down here, this far south, but is worn out with wind and tempest and weather; all is flotsam and jetsam. They leave their rags and tatters here; why do we have to be dressed? The sun is hot enough; why can’t we run naked in our own country, on our own land and work out our own destiny? … This land was last discovered: Why? A ghost land, a continent of mystery: the very pole disconcerted the magnetic needle so that ships went astray, ice and fog and storm bound the seas, a horrid destiny in the Abrolhos, in the Philippines, in the Tasman seas, in the Souther ocean, all protected the malign and bitter genius of this waste land. Its heart is made of salt: it sudenely oozes from its burning pores, gold which will destroy men in greed, but not water to give them drink. Jealous land! … Bitter dilemma! … Our land should never have been won.’

—Christina Stead Seven Poor Men of Sydney1934(Preface, Wilderness page 7)

THE PREFACE to this ‘blurred map of landscapes still unmapped’ is introduced by a series of rhetorical questions, posed in 1934 in Christina Stead’s novel Seven Poor Men of Sydney. It is given to her character Kol Blount, a crippled youth, to voice certain philosophical concerns while a group of friends entertain themselves in the gardens of an insane asylum by telling stories. Why are we here? Why and how do we carry with us the vestiges of our older civilisations as we attempt to work out our destiny? Why is it that this land, with its ‘malign and bitter genius’ protected by such formidable expanses of ocean, was the last discovered by the European colonial powers, and what are the consequences of this? That which the novelist Stead describes as a ‘bitter dilemma’: the conundrum of a land that showers riches on humanity while denying it the basic sustenance of water; and which in 1965 the poet Judith Wright termed its ‘double aspect’, the conflicting themes of freedom and exile, have exercised the imagination of many Australian writers since the first words were written in Australia. What importance Stead might have continued to attach to her metaphor is, after her death, uncertain, but the the questions remain. Some writers, including the novelist and poet Randolph Stow, have chosen to infer the presence of a higher power in the land- scape and, consequently, in humankind (‘What is God, they say, but a man unwounded in his loneliness?’), others, more fashionably, to answer by way of more mechanistic modes.

In this attempt to survey some of the ways in which writers have addressed these questions and contradictions, the definition of ‘landscape’ has been expanded somewhat. ‘A prospect of inland scenery, such as can be taken in at a glance from one point of view’, states the Shorter Oxford. But in Wilderness the concept of ‘landscape’ encompasses the Australian continent’s relative distance and isolation from other Western nations; the facts of its colonial history as determined by its unique geography (which includes its position in Asia and Oceania); the effects of colonial invasion on a previously isolated indigenous population; and, finally, the demography of its urban populations and the way they have formed as a result of that geography. ‘Landscape’ here means Australia’s place in the Southern Hemisphere both as an island—with the relative insularity that that implies—and a continentwith its corresponding potential for cultural and geographical diversity.

Though remaining predominantly English-speaking and urban, like their parent-culture, the writers who have produced our literature of landscape were only rarely just undertaking an intellectual and aesthetic survey of the countryside from a book-lined study window, perhaps between jotting notes for a sermon. Romanticism—which has been defined by some as a high development of poetic sensibility towards that which is remote or distant in time and place—gained a foothold only in the rather more modified and mundane form of the bush myth. The idealised and heroic figures of classical art and literature never had a chance to take firm root in Australia because, paradoxically, of a lack of distance, both chronological and real. Where there is little history, there is little myth. Where a society is newly established, it is necessary for most of its members to get their hands dirty. The ghosts of Aboriginal culture were invisible to the European eye. The Australian landscape and the challenges it presented were more immediate in time and space to its writers than the fields of antiquity were to English scholars, and even, in many cases, than the landscaped vistas and tasteful Grecian follies of his park were to that English guardian of culture, the aristocrat. What did become mythologised or romanticised, perhaps, were race memories of distant ‘Home’. The sense of truly belonging somewhere else, like a child’s disconsolate fantasies of being adopted, lingered long after Australian-born generations had established themselves. All Australians, bar the country’s original inhabitants, have at close proximity the sense of inhabiting an alien context.

It has been argued both here and elsewhere that the ‘Australian’ character (and consequently its literature) has been formed to some extent by the process of a physical and intellectual grappling with a unique landscape, and one not experienced before by Europeans. While on one hand the development of Australian society could be said to fit predictably enough into the pattern of shifting populations and colonial expansion that has occurred in the last half of the millenium, this is not sufficient in itself to explain the formation of a collective cultural psyche. There have been discernible parallels with the American and Canadian experiences of settlement, and similarities with other emerging post-colonial cultures. But as these other emerging nations differed from each other, according to their various inhabitants and environments, so does Australia from them.

And yet, ultimately, however it is defined, we are forced to recognise that the Australian ‘landscape’ is something both less and more than geopolitical factors and deterministic forces, or even psychosexual ones. The Aboriginal idea of landscape has little to do with any of these concepts. It could be argued that a germ of conflict and mystery still inhabits the work of Australia’s writers today, springing from the influence of the continent on the interior landscape of our collective psyche. This impact must be considered when we ask, as a corollary to Stead’s questions, who are ‘we’? And who do we speak for when we attempt these answers? ‘Landscape’, as many poets and novelists would argue, has become a formative concept in the Australian metaphysical dialogue. If there is a soul to the Australian people, then, according to the work of many of the writers surveyed here, it is a soul shaped by landscape.

(Wilderness page 232-233)