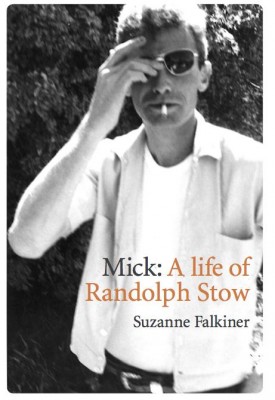

MICK: A LIFE OF RANDOLPH STOW

MICK: A LIFE OF RANDOLPH STOW

University of Western Australia Publishing

February 2016

ISBN: 978-1-74258-660-1

Available from:uwap.uwa.edu.au

Available in February 2016 from University of Western Australia Publishing

‘A PRIVATE rather than a social observer, he confronts us, in achingly beautiful writing, with men who are alone, adrift in the outback, the desert or the jungle, searching for peace within themselves and with God. Like their search for love, their search for personal reconciliation is seldom rewarded, but always intensely and empathetically imagined. His novels and poetry embody a uniquely rich and strange account of the land and people of Australia that we can ill afford to lose.’

—Anthony J. Hassall

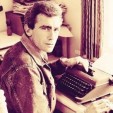

RANDOLPH STOW was one of greatest Australian writers of his generation. His novel To the Islands – written in his early twenties after living on a remote Aboriginal mission – won the Miles Franklin Award for 1958, and in 1979 he won the Patrick White Award. In later life, after publishing seven remarkable novels and several collections of poetry, Stow’s literary output slowed. This biography examines the productive period as well as his long periods of publishing silence.

In Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow, Suzanne Falkiner unravels the reasons behind Randolph Stow’s quiet retreat from Australia and the wider literary world. Meticulously researched, insightful and at times deeply moving, Falkiner’s biography pieces together an intriguing story based on Stow’s personal letters, diaries, and interviews with the people who knew him best. And many of her tales – from Stow’s beginnings in idyllic rural Australia, to his critical turning point in Papua New Guinea, and his final years in Essex, England – provide us with keys to unlock the meaning of Stow’s rich and introspective works.

—UWAP

Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 2016: Book Extract: Randolph Stow’s farewell to Australia for a life of self-exile, by Suzanne Falkiner

SYDNEY REVIEW OF BOOKS: Randolph Stow’s Trobriand Islands, by Suzanne Falkiner

Late Night Live with Phillip Adams, ABC Radio National, podcast: The Lost Life of Randolph Stow

Westerly Magazine: ‘Randolph Stow: Pictures, Letters and Conversations’

The Randolph Stow Memorial Lecture, delivered by Suzanne Falkiner at the Perth Writers Festival, 21 February 2016.

‘Getting to know Mick’, Marginalia, UWAP, February 2016.

What they said:

— ‘One of the finest biographies I have read over the last five years…. Published by UWAP, it is a formidable piece of writing and research, exploring the … life of one of Australia’s greatest writers. The work is intelligent, thoughtful and accessible: the exact things that cultural criticism needs to be.

— CHRISTOS TSIOLKAS, The Saturday Paper, 16 November 2019

The overriding virtue of this book is Falkiner’s steady trust in the intelligence of her readers. She spells very little out, presenting us instead with this carefully curated wealth of textual evidence. There is consideration and mannerliness in this, towards her subject as much as towards her readers; she keeps impertinent speculation about Stow’s spiritual life, his emotional life, and his sexuality to a minimum, quietly setting down such evidence as exists in his own words and in those of the people who knew him best. …. Falkiner’s style is literate but lucid, low-key and unassuming. As a compellingly readable feat of painstaking Australian literary scholarship, this book should take its place alongside David Marr’s Patrick White: A Life (1991), Hazel Rowley’s Christina Stead: A Biography (1993), and Nadia Wheatley’s The Life and Myth of Charmian Clift (2001).

—‘A Huge Subterranean World’, by Kerryn Goldsworthy,

Australian Book Review, March 2016, No. 379

Falkiner’s biography is a meticulously researched recount of a complicated but important creative life. …as a complimentary narrative to the critical evaluations of Stow’s work …, Falkiner’s Life is of inestimable worth.

—Phillip Hall, ‘Review’, Cordite Poetry Review, 23 March 2016

With the publication of Suzanne Falkiner’s Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow, readers have the opportunity to learn a great deal about one of the greatest Australian writers of the 20th century. …After years of exhaustive archival research, international travel and extensive interviews, Falkiner crafts a credible and moving portrait of a brilliant, sensitive, complex man. This biography is a significant contribution to Australian literary studies.

—‘A Book of Revelations’, Bernadette Brennan, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 25, 2016

For those of us who consider Randolph Stow one of the secret kings of 20th-century literature, not just a damaged wunderkind of its Australian branch, Suzanne Falkiner’s new biography of the writer inspires both excitement and trepidation.

The excitement arises from the knowledge that this is the first full-length life of Stow to appear. Finally we can see how the individual aligned with and departed from his work. Finally we have some clarifying sense of the wounds that shaped and animated Stow’s poetry and fiction. The trepidation arises from the same revelations. …Falkiner has done an admirable, if impossible, job in these pages….This is the life of Stow we needed: empirical where he was myth-making, expansive where he was elliptical, prosaic where he was poetically inclined….

Falkiner …tracks him through his immense North American road trip care of a Harkness Fellowship during the mid-1960s (Merry-Go-Round was written in a white heat during a couple of months’ stay in New Mexico), and then on to London and Leeds, where he saw out the 60s in the company of composer Peter Maxwell Davies and a cast of scholars, gypsies and scribes. We glimpse him drinking whisky with Thom Gunn and recovering with Sidney and Cynthia Nolan; being psychoanalysed by Anthony Storr ….it takes Falkiner’s sleuthing to show how and why Stow found a place in East Bergholt, Sussex, and then in nearby port town Harwich to be an approximation of…home.

—Geordie Williamson, ‘Randolph Stow biography…reveals a wounded man’, The Australian, 2 April 2016

….one of the finest literary biographies I’ve read. Scrupulous in detail. Superb in tone. Breathtaking in research.

—Peter Goers, The Evening Show, 891 ABC Adelaide

Mick has been published splendidly in hardback, with a striking cover of a blurred, sun-glassed Stow; it is extensively referenced and comprehensively indexed. …a major contribution to the field of Australian literary studies…[and]…the first biography of a significant Australian writer…

—Nathan Hobby, Westerly, July 2016

Suzanne Falkiner has written a magnificent biography of a mysterious and brilliant Australian writer, and one which should encourage readers to revisit his work. It is not only extensively researched and detailed…but the facts are woven with intricacy and skill to create a complex portrait of the man.

—Sue Bond, ‘A review of Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow by Suzanne Falkiner’

Compulsive Reader, August 20, 2016

The great gift this year was Mick: A life of Randolph Stow (UWA Publishing, 3/16) by Suzanne Falkiner, which provides the material for a new look at this much-loved writer. Falkiner recovers Stow from the archive, including his own wonderful correspondence, and travels in his footsteps from Geraldton to Harwich and all the way to the Trobriand Islands. She is good on settings, knowing how someone can be out of place where they are most at home, and writes about his loyalties and antipathies with empathy and a dry wit that Stow would surely have appreciated.

—Nicholas Jose

2016 Books of the Year, Australian Book Review, December 2016, no. 387

It has been a rich year for fiction, but the book which stands out most for me is a biography. Suzanne Falkiner’s Mick is a beautiful and detailed examination of Randolph Stow’s life, supported by a wealth of research. This is a work which not only feels overdue, but is touching in its intimacy.

—Catherine Noske

2016 Books of the Year, Australian Book Review, December 2016, no. 387

One of our best writers gets his deserved due in Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow by Suzanne Falkiner.

—Stephen Romei, Literary Editor

‘Holiday Reading’, The Australian, 10 December 2016

Suzanne Falkiner’s prodigious biography of Randolph Stow is a book long awaited by many; not just the literati of his native Australia but those countless readers who feasted on his novels and wondered what kind of person could write with such imaginative power.

….Against significant odds, she has done a masterful job in painting a portrait of one of Australia’s most revered writers, somewhat akin to what compatriot David Marr did for Nobel Prize–winning author Patrick White. It will no doubt send readers scurrying back to Stow’s novels, which, as Marr once said, is the best news a biographer can hear.

— John Burbidge, World Literature Today,

University of Oklahoma, USA, January 2017

Read an extract...

CHAPTER 14: Troppo Troppo

“All right,” he said, “if you know so much, have you ever heard of a piece of music marked troppo agitato?”

“I don’t think it’s possible,” I said.

“I think it is. I want to hear it. At the end, all the instruments would be in bits.”

“I’ll bet it’s been done,” I said.“Ah, but this would be tropical,” he said. “I can see it,” he said. “The glue would melt in the heat, and the wood would warp, and the strings would rot away with damp and snap, one after the other. The brass would turn green, and mildew would be growing out of the woodwinds. When it was finished, the instruments would be thrown in a heap, and they’d begin to sprout and turn into the trees they were made from. And reeds and vines, and the wind would blow through them and the birds would come. That part I’d mark finito, or troppo troppo.”

— Visitants, 1979, page 48

After his last diary entry at the end of June, Stow’s thoughts and movements are difficult to trace with any exactitude. The last of his fortnightly letters that Mary Stow kept from this period was dated 22 May 1959. Helen, his sister, remembered that her mother subsequently received others, but destroyed them, evidently finding their contents disturbing, or ‘not making much sense’.

Sometime in 1960, probably in England, Stow would add some fragmentary notes — undated memoranda — to his diary about his remaining time in the Trobriand islands:

Remember the green fireflies like eyes in the dripping trees—the owl — the smell of palm leaves drying.

At Toboada in August the flowers were out—vinca, convolvulus, hibiscus, painted lady, and some kind of pea like a violet, very sweet smell.

Bwita too, a fragrant cream coloured flowering ficus. Very windy. Stayed there three weeks. Then Sinaketa, on the sea. When tide is out pigs went to waterline foraging among the mussels etc. Reef beyond at waterline. Awake all one night and saw before dawn Katamapula Guyan take out his canoe fishing. Extraordinary blue world.

Vakuta three weeks. Remember the terrible broken and desert coral forest. Surf smashing on the forsaken cliffs. Kitava, and the strange hospitality and character of Kam the King. Iwa—island left alone by Europeans—high coral cliffs, grey with just a little vegetation, rising out of a sea that was clear as the air itself, or clearer, and showed the fish and coral as if through a magnifying glass. A long moonlight trip back to Kitava, not a disturbance on the sea but our own wake. Then the sickness — cold, all day and night—and finished or tried to at Muwo.

Remember Dokonikan cave, the one at Kitava — old woman at census whose husband and son had died—evening when the lamps were lit—changing colours of palm fronds at different times of the day—much else. Was happy, often.

Probably, therefore, it was sometime in late June or early July, in an abnormally rainy period while they were still at Omarakana, that the milamala occurred. In 1959 it was the turn of Liluta, some five miles away, to organise the yam harvest festival in the area.

However, there had been a longstanding feud, dating back to Malinowski’s day, between Mitakata and Iobokwau’u, the present chief of the Kwainama matriline (or sub-clan) at Liluta (who, through intermarriage, was the son of To’uluwa, the previous Guyau of Omarakana). Chief Iobokwau’u, an active old man, had frequently visited Julius and Stow at the Omarakana rest house, but would never enter the village proper to talk to Mitakata.

Now, at Liluta, wrote Charles Julius, a huge central platform, especially built, was laden with yams, pigs, taro, sugar cane, betel nut and many other good things, in tribute to Mitakata, who was asked to make magic to improve the weather. There was much blowing of conch shells as the men of the other villages marched in, with Vanoi leading the Omarakana delegation — Mitakata had stayed behind, evidently too old to travel the distance. This festival would for last several days, and would involve night-long singing and dancing and much courting and sexual activity among the younger people.

At Sinaketa, the fishing village in the southern part of Kiriwina where pigs foraged at the waterline, Stow and Julius would pass the next six weeks. Here, awake all one night, he watched a lone fisherman in his outrigger slip out before dawn on a motionless silver sea — the still moment when, in Trobriand belief, the soul sets off by canoe from Bomatu Point in the northeast for the ‘isle of the dead’, embodied by Tuma Island some twenty kilometres to the west. In this ‘extraordinary blue world’ the two men stayed through 25 August to 8 September, witnessing the occasional arrival of Kula canoes on their long journey from the D’Entrecasteaux and Amphlett islands to Kitava, bearing soulava necklaces for ceremonial exchange, while the mwali armshells passed in the opposite direction.

For two weeks, until 22 September, they stayed in the village of Okina’i on the island of Vakuta, across the narrow strait at Kiriwina’s southern tip. Now came a steady build-up of ominous images: a product perhaps of Stow’s own darkening mood, or of the uneasy atmosphere that sometimes prevailed—due to some quarrel or incident of sorcery—between the small island communities. Stow later remarked in a letter to anthropologist Michael Young on the ‘strangely redecorated’ church at Kaulaka, a village toward the ocean side of the island, and a similarly abandoned structure in their own vicinity, where the ghosts of ‘dimdim’ religious ceremonies were held. In Visitants he would add to this ‘church-casino’, drawn from life at Kaulaka, the bizarre carved figure of a wartime pilot crucified on a wooden plane.

….. After four months in the field, Mick’s physical health, like Julius’s, was deteriorating. His mother had already mentioned his dysentery, an affliction often accompanied by feverish symptoms and weakness. Earlier, both men had suffered from flu, and Stow an infected hand. The local diet — heavily dominated by yams, taro and green vegetables, with bananas and coconuts, supplemented by fresh fish (when available) and tinned meat — was ostensibly healthy, but it was lower in protein than most Europeans were accustomed to. Stow, with an inclination to ‘live native’, was by this date suffering from vitamin deficiencies and malnutrition.

Perhaps it was this feeling of debilitation that led him to stop taking his daily Chloroquine tablet, a prophylactic against malaria. With its unpleasant metallic taste, Chloroquine’s side effects sometimes include headaches, blurred vision, nightmares and gastro-intestinal problems, as well as — with long-term use — a slow onset of mood change, anxiety and depression. At any rate, at some point Stow may have contracted the mosquito-borne malaria parasite, which for now lay dormant.

LANDFALL

And indeed I shall anchor, one day—some summer morningof sunflowers and bougainvillea and arid wind—and smoking a black cigar, one hand on the mast,turn, and unlade my eyes of all their cargo;and the parrot will speed from my shoulder, and white yachts glidewelcoming out from the shore on the turquoise tide.

And when they ask me where I have been, I shall sayI do not remember.

And when they ask me what I have seen, I shall sayI remember nothing.

And if they should ever tempt me to speak again,I shall smile, and refrain.

—Outrider, 1962

Copyright: may not be copied or reproduced

without written permission.