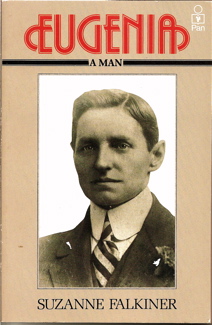

EUGENIA, A MAN

EUGENIA, A MAN

Pan Books, Sydney

1988

ISBN: 0330271121 paperback

Sydney gay and lesbian history, Transsexuals

Available from:briobooks.com.auwww.booktopia.com.auwww.abebooks.com

New edition ebook available from BRIO BOOKS

Paperback edition available via BOOKTOPIA

…Woodrow asked me how so, but the whiskey was at work and I felt too deaf to tell him; but what I would have said was: as truth is non-existent, it can never be anything but illusion—but illusion, the by-product of revealing artifice, can reach the summits nearer the unobtainable peak of Perfect Truth. For example, female impersonators. The impersonator is in fact a man (truth), he recreates himself as a woman (illusion)—and of the two, the illusion is the truer.

—TRUMAN CAPOTE Answered Prayers

Born in Italy in 1875, EUGENIA FALLENI migrated to New Zealand with her family at the age of two. Settling in Wellington, in the south of the North Island, the family were hardworking, law-abiding and respectable-except for Eugenia, who grew up restless, wilful and undisciplined. She wore boys’ clothes when she could and repeatedly ran away from home. Dressed as boy, on one occasion she got a job in a brickyard, at another time in a laundry. Small, wiry, strong, and unable or unwilling to learn to read and write, she was considered ‘simple’, but her tomboyish eccentricities were initially regarded as harmless enough. In her teens, and again dressed as a boy, she ran away to sea.

Some years later when she turned up in Newcastle, a seaport on the south eastern coast of Australia, having apparently worked in the intervening time as a cabin boy. Soon after she gave birth to a child. Although she herself would tell varying stories as to the identity of the father, the truth was that she probably had been raped on board ship and, once pregnant, put ashore when the ship docked in New South Wales.

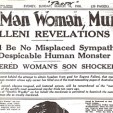

Eugenia fostered the baby to an Italian family, and from then on, for nearly twenty years, she continued to live as a man. It was this same Eugenia, who as Harry Crawford, called by the newspapers ‘The Man-Woman Murderer’, was later tried for murdering the woman living with him as his wife.

What they said:

‘Lucidly written by a trenchant and conscientious writer, Eugenia, A Man is undoubtedly the fullest and fairest account of the curious and tragic life of a transsexual in Sydney at the turn of the century.’

—Mark Try Campaign

August 1988

‘Suzanne Falkiner’s treatment of this story is impressive in several ways. It skilfully alleviates the monotony of old documents; it traces a complex life with reportorial skill, it makes this past sequence a matter of present concern and enlightenment….As the author of a good book, and, rarer still, a good book about crime, Falkiner deserves both praise and respect.’

—Stephen Knight The Age Monthly Review

October 1988

‘Well-researched and clearly written’

—Peter Corris The Weekend Australian

10-11 December 1988

‘Thoughtful, absorbing’

—Sydney Morning Herald

17 December 1988

Read an extract...

I CLOSED the endless blurred carbon sheets that were the trial transcript and put a rubber band around them. A kaleidoscope of images plucked from the mundane suburban lives of Eugenia’s neighbours and acquaintances, they had revealed as much by what was not in them as by what was. Eugenia had said little for herself. The defence counsel had obviously decided that she was an unsafe witness to put in the stand. No alibi was offered, no extenuating version constructed of what might have happened. During her three months of imprisonment before the trial, wrote Moran, Eugenia gave varying accounts of her movements over the period, all of them foolish. Her daughter Josephine was not called upon to testify on her behalf. Maddocks Cohen’s efforts in the Police Court to cast doubt on the forensic evidence and the identification of Eugenia by witnesses were not very energetically pursued by the defence.

Facing Eugenia in the crowded courtroom was the daunting spectacle of the bewigged judge, dressed in scarlet, and her own counsel, in black—no longer the familiar and experienced Maddocks Cohen, but a new and rather inept younger man, McDonnell. The jury had filed into the box: her handpicked jury of younger men, true, but who could tell how they would react? And in the gallery, the blind, staring face of the public.

The last day of the trial, Wednesday 6 October 1920, had been only a little over a week after the day, three years before, that Eugenia and Annie had set out together for the Lane Cove River. On Oxford Street the people came and went, perhaps aware from the crowd outside that something unusual was happening in the Darlinghurst Courthouse. But the thick sandstone walls and columns kept their counsel for the moment. Inside, insulated, the solemn processes of the law ran their course. Eugenia sat in the dock, watching in silence, as two men in wigs and gowns argued out her fate. The court stenographers waited.

For Coyle, the prosecutor—experienced, theatrical, meticulous—there was the challenge, perhaps, of an unusual case, but little more. The evidence against the prisoner before him was damning. He would be stern but scrupulously fair, according to his own lights. The outrage that this woman had presented to the established order would work against her without his help. And he was an honourable man by reputation, who would himself ascend to the bench a few years later.

‘I find it difficult,’ he said ingenuously in his opening remarks, ‘to refrain from referring to the accused as a man, but when I do, you will understand that I refer to the accused.’

The women in the audience craned to look.

IN the State Library, the Australian Year Book of 1919 describes the women’s prison at Long Bay as ‘a well-designed reformatory for females’. Recent innovations included the then revolutionary concept of segregating prisoners according to the seriousness of their crimes, and ‘reform rather than retribution’ was a stated aim. A random survey of the records still available reveals that many of the women who passed through its gates were little more than minor casualties of a society where respectability in women was prized.

The photographic record books in the State Archives display an endless succession of haunted, often simple-minded faces of young girls and lined and battered older women. The names are sometimes Aboriginal, sometimes Irish. Sometimes the women are described as being in domestic service, more often they are unemployed. Usually they have little education. The crimes they have committed are often little more than crimes against the accepted female role: vagrancy (the sin of being without a home); drunkenness. riotous behaviour and indecent language (the sin of being ‘unladylike’), ‘creating a nuisance’ (a euphemism for prostitution), and performing abortions. Others have been convicted of petty theft of the type that usually accompanies poverty – pickpocketing, shoplifting, stealing from places of employment by servant girls. For crimes like these, some of the women have over a hundred convictions.

The more serious offences include assault, receiving stolen goods, passing false cheques and, very occasionally, manslaughter (often middle-aged women whose other convictions suggest that they were abortionists).

The vast majority of women passing through the reformatory in the early 1920s were serving minor sentences; some of only twenty-four hours or a few days, others of a few weeks or months. In this rogues’ gallery, the female murderers stand out in their scarcity.

Eugenia also left her fleeting mark in the ponderous Department of Corrective Service ledgers in the State Archives; large, bound volumes such as the Entrance and Discharge books for the State Reformatory for Women, Long Bay. As late as 1921 these still had columns bearing the convict legend ‘Ship and Date of Arrival’, now crossed out and amended to ‘Place of Birth’. These enigmatic entries do little but affirm that, yes, on such-and-such dates Eugenia was admitted and allowed exit through these gates to attend her hearings and trial, among the seemingly endless stream of women arrested for petty crimes, each marked off and their sentence noted by the same deliberate nib of an unknown clerk, each entry representing a life story equally unknowable.

The last red ink notation in the Entrance book for Eugenia (entry 1012), dated 6 October, reads ‘Sentenced to death’.