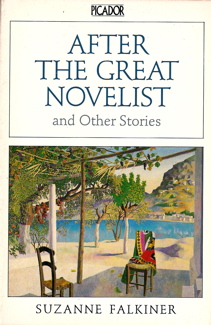

AFTER THE GREAT NOVELIST

AFTER THE GREAT NOVELIST

Picador

1989

ISBN: 0330271253

Short stories, travel writing

Available from:www.abebooks.com

AND OTHER STORIES

‘…Suzanne’s book is one of the most intriguing and satisfying I have read in a long while, not least because it defies classification. Its stories lie somewhere between the very best travel writing and short fiction. They stretch the reader’s perceptions and imagination. Perhaps—if Suzanne will excuse me—they can be called traction.

In a relatively short time, Suzanne Falkiner has become one of the most complete writers in Australia, covering more literary territory than anyone else currently writing here. She has written a novel, Rain in the Distance, compiled an anthology of women’s fiction, Room to Move, written a non-fiction book Eugenia, A Man, and three other non-fiction books.

I’ve been reading her work in manuscript and published form since 1980. From the beginning, it made a strong impression on me, particularly the calm, searching, ironic style seen perhaps at its best when her character, Stork, describes the behaviour of predatory men, here and abroad.

In After the Great Novelist I think all her previous work and intentions have reached fulfilment. The stories here glance off the landscape, the towns, the people, like vivid dreams. Unlike other contemporary travel writers —Theroux, Morris, Newby, Raban—Suzanne Falkiner doesn’t confront her new experiences so much as absorb them and use them to understand the smaller picture, the single lived life, as well as the broad canvas. Perhaps Bruce Chatwin is her nearest contemporary, but even he shied from the personal and self-revelatory in his work.

The title story ‘After the Great Novelist’ (the great novelist in question being Graham Greene, and the country, Haiti), will probably get the most critical applause of the stories in this book, but my favourite is one titled ‘Signs’ (the semiologists will approve) which begins with a sign tacked to the wall of a gringo restaurant in Guatamala, and ends with a sign on the wall of the cemetery at Guayaquil, the city of thieves, in Ecuador.

The first sign said:

LOST!

By mistake I lost my Babie!

You know how these partying nights are. Whoever has her please return, I miss her.

Her name is Sunrise. Return to Angel staying at the house 200 yards behind Mama Ramere’s.

The sign on the cemetery wall said:

PAY ATTENTION.

There you have the whole picture.

—Robert Drewe Sydney Morning Herald

22 April 1989.

What they said:

BOOKS about travel invariably fall into two categories: the dry-as-dust type reeling off reams off facts and figures or the reflective story that captures the essence of a place, its people and those who gaily venture forth into its foreign ways and byways.

This amusing and engrossing collection falls into the latter category and takes us, with penetrating panache and an acutely observant eye, to Istanbul, Italy, Morocco, North and South America, Haiti and Australia.

The author, who was born in Sydney in 1952, writes with grace and detachment and, at times, an endearing staccato quirkiness that superbly high- lights an unusual moment, incident or personality.

In the title story, the narrator follows in the footsteps of novelist Graham Greene in the sinister decadence of Haiti and toys with the reader about the identity of one of the characters. Is he the same man mentioned years ago in Greene’s novel’?

Where the book excels is in the skilful blend of people and places, as in ‘The Sheep in the Bathroom’ and ‘The Blue Hotel’, both set in Morocco. There the traveller befriends Arabs and has to come to terms with the rituals of Muslim culture, which she realises are in a sense no more untoward than the customs of New York described in ‘The Writing Class’.

Particularly moving is ‘Landscape with Figures’, a story about a white community and Aborigines co-existing in the isolation of a settlement in central Australia. It is brutally frank and throws disturbing light on the all too familiar pattern of the effects of a clash of cultures in remote areas.

As the book’s blurb so aptly puts it, the stories are built round the poignant reflections and precise observations of a writer for whom travelling is a means of apprehending experience.

All in all, the book is a delightful read and conjures up pleasant thoughts of how enjoyable and fulfilling it would have been to accompany the author on her travels.

—Edward Masson The West Australian 5 August 1989

‘..a finely tuned sense of social observation, a spare writing style and an eye for the quirky, the disquieting and the idiosyncratic…’

—The Sun Herald 14 May 1989

‘a welcome rendez vous with a perceptive and observant mind.’

—Dorothy A. Fontaine Antipodes USA Winter 1990

Read an extract...

AFTER THE GREAT NOVELIST

HAITI: ‘After the Great Novelist’

On the second evening after Stork’s arrival, a thin wisp of a man in a white suit hovers behind the chair opposite hers in the hotel dining room. In his hands is a silver mounted ebony cane, at his throat a rose pink scarf. Stork is sitting at a white-clothed table, waited on by attentive staff, also in white. The dining room is almost deserted; the tourist season has not yet started. The click of her soup spoon against the white china bowl seems abnormally loud.

The man before Stork has a clever, haughty, almost simian face, and he holds his cane delicately in front of his slim body. His head dips at the end of a thin neck and he speaks in a soft, lilting voice. He is, he tells her in French, a journalist. He used to be in the Ministry of Culture. He believes that she is a journaliste also?

Stork has a memory of saying some such thing to Alix a while ago. Something about a travel article for a magazine. Alix is a nightclub singer, an almond-eyed, coffee-coloured man who started a conversation a little earlier in the evening when he found her scribbling behind a tourist newspaper in the lounge. As well as being a nightclub singer, he explained (would she like to come up to a little club in the hills and hear him sing?), he also works with the World Health Organisation. He was over-complimentary about Stork’s hesitant French.

It occurs to her now that the hotel made famous by the great novelist is a place where she could be any of a number of things by the end of the evening. A failed adventuress, a sociologist even. But not a freelance writer who never managed to finish a story.

Stork is a journaliste, the man in front of her reiterates with some determination. She is, in addition, an australienne. May he sit down? Does she work for the Daily Telegraph in Sydney? He has once written an article for the Daily Telegraph in Sydney. Would she like to meet the head of the Government Tourist Bureau; would it be useful? In seconds he has acquired for her a glass of white wine and he kisses the air a little above her hand when she offers it to him to shake. The hand that takes hers is dark and thin and has extraordinarily long fingers.

He has an art gallery, too, he tells her. Is she interested in the local art? As he is also the ex-Deputy Minister for Culture, it is his duty to help her in any way he can.

MARRAKECH: ‘The Sheep in the Bathroom’

The sheep in the bathroom looks irritated; it stamps its hoofs on the tiles and tosses its horns. A tattered, rangy looking brown ram with a mean yellow eye, it stands with the rope that ties it to the white china washbasin hanging limp between its legs. It watches us suspiciously. Stamp stamp on the clean white tiles. Perhaps it knows. Perhaps it is bluffing, and the anger and the glint in its eyes is really fear. Tomorrow, according to a precedent of sacrifice set by Abraham, the blood of a thousand rams will run in the gutters. After being half-dragged, half-carried up the stairs to the apartment, it must sense that it will never make the descent. It is a big animal. It stares at us with its head up, unblinking. Baleful. Unforgiving.

We go back into the living room and drink tea.

NEW YORK: ‘Homesickness’

The inside of the lift in the Guggenheim Museum is bright orange, like the inside of a tomato sauce bottle.

‘This lift is like the inside of a tomato sauce bottle,’ I say to the boy who is pressing the buttons. He grins. Too late I remember it is not a lift but an elevator, and not tomato sauce but ketchup.

The boy breaks into a slow smile and he starts to laugh. ‘Man, you ever bin inside a tomato sauce bottle?’ He giggles all the way to the top.

Not so the man in the Museum of Modern Art. Nondescript in a clean shirt and slacks, he is sitting at the next table in the cafeteria talking about his job. He makes pornographic films, he says.

‘Clean stuff,’ he says.

He is talking to his friend, whom he has not seen for a while.

‘Middle-of-the-road stuff, really. None of that sick stuff.’ He considers. ‘Yeah. I make middle-of-the-road pornography.’

His friend’s wife arranges parties. His friend helps her.

The one they are working on now is not until next year, he says, but it takes a while to get organised. This isn’t one of your $50,000 parties, this is one of your $130,000 parties. A fiftieth wedding anniversary for a businessman and his wife. The businessman wants costume dolls representing famous lovers for all the tables. That takes a bit of planning; his wife has to find someone to make all those costumes, buy all those dolls.

He pauses. And she hasn’t even thought about the flowers yet.

‘You from England?’ The boy looks spanish, looks seventeen or eighteen. He is badly shaven, but his eyes are bright.

‘No,’ I say. ‘Where, then?’ ‘Australia.’

‘Well, near enough.’

Then he appears to think about what he has said, and grins again.

‘Well, you speak like the English.’

He has a brother in Australia, he says, who works for the government somewhere in Sydney. He does not know where in Sydney, because he hasn’t written to him in six or eight years. But he knows where Australia is.

‘You know,’ he tells me confidentially, ‘whenever I think of Australia I think of ice.’

‘Maybe you’re thinking of Antarctica,’ I say.

‘Yes, I know it’s all wrong, but I still get this image of lots and lots of ice.’

He hands me my package of fried chicken. I smile at him and he smiles back. So maybe his wilderness of the mind, his last frontier, is made of ice and called Australia.

My metropolis of the mind is called New York.

BRAZIL: ‘A Thousand kilometres of River’

In the town of Manaus, the river bank was lined with a myriad of boats, water hyacinths, shacks on rafts, and naked children who swam in the oily water. The rain forest came down to the river’s edge in places, even invaded the shallows; you come across the shells of rusted metal ships with trees growing out of them. It took about half an hour to cross by boat from one side of the river to the other.

Outside the clearing which contained the town, the canopy of the forest met overhead to block the sky.

But from the air, coming in, it looked different. Then the forest was a smooth carpet of green, like moss, stretching as far as the horizon in all directions. The shining band of the river formed a meandering roadway through it, coiling like a snake.

At the harbour, the vultures perched on top of the market building and kept an interested eye on what passed below. Or perhaps they only watched the glittering silver fish that were unloaded from dug-out canoes on the river. Ricardo told me the market building was built by a French architect during the rubber boom. He was called Eiffel, he said. But that was before the Javanese learnt to grow rubber more efficiently than the local people. Now its Art Nouveau trimmings were ramshackle, and the glass was broken in the skylights. These days the inhabitants of the town lived on dilapidated house-boats or in wooden shacks built on poles on the river banks. In the evenings, as I passed, they sat in their plastic-bound metal rocking chairs outside their houses, sipping puddles of thick black coffee from the bottom of tiny cups, while the vultures flapped and squabbled at their feet.

Ricardo spent most of the first twelve years of his life on the river. His father had owned a boat company that ran supplies to the Indian villages. Sometimes the tributaries meandered so much that a single voyage would last a year. Now Ricardo was an interpreter in one of the bigger hotels; he wore neat new clothes and was as sharp as a rat with a gold tooth. In the evening I would see him leaning over a cafe table in the town, skinny and earnest, talking to one of the young Brazilian girls. Then he pretended not to see me.

ITALY: ‘Umbria’

Later, while Eva was still sleeping, I sat with Julia and drank tea on the stone steps. The sky was a hazy blue, but then a wisp of dirty brown smoke began to creep into it. The fires had apparently restarted with the evening breeze. Within minutes the smoke was a column, and then, in the distance, there were flashes of orange amid the dead vegetation. Suddenly there was flame soaring above the distant trees, you could hear the roar of it. The smoke hung in a thick pall. Julia was crying again. We seemed safe enough where we were, but the beautiful valley was being destroyed.

From what I could see, the wind was blowing the fire back onto the area that was already burnt, and I told Julia that it would burn itself out, and eventually it did. I remembered that in Australia fires must burn through forested areas at times, or there is never any opportunity for new growth, but I did not know if this was true of the oak and coniferous forests of Italy. It was no comfort to Julia.

Tranquilo, Emilio’s brother, pointed out that now everyone used bottled gas for cooking. The dead wood was not picked up any more, so the forest was flammable. The fire had been caused by the man who ran the petrol station, Tranquilo reported. The man had been burning off.

Emilio, a tall grey stork of a man who never married, had always looked after Julia, and did whatever work was necessary around the place. She was alone for the first year or two, then Nick the painter came to stay with her.

Emilio was jealous. He stopped coming.

Eventually, according to the story I was told not by Julia but by someone else, the Australian feminist writer who lived across the valley fixed it all up. How could Emilio leave the Signora alone? Everybody was saying that he had made advances to her and she was forced to tell him to go, she informed him. It was no good, she said, that such a story should go around.

So Emilio went back.