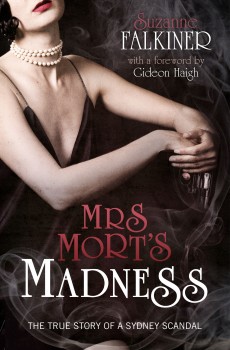

Mrs Mort’s Madness

Mrs Mort’s Madness

XOUM

Available December 2014

ISBN: 9781922057914

Biography, History of Sydney, Non fiction, True Crime, World War I

Suzanne Falkiner

Foreword by Gideon Haigh

The True Story of a Sydney Scandal

MRS MORT’S MADNESS is now available from BRIO BOOKS

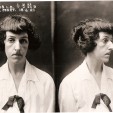

Four days before Christmas in 1920, Dorothy Mort shot her lover dead in cold blood. The tragic end to her affair with dashing young doctor, cricket star and war hero, Dr Claude Tozer, scandalised Sydney. Dorothy’s respectable husband was devastated.

Following a trial that mesmerised the public and sent the media into a frenzy, the troubled North Shore mother of two and budding actress was declared ‘not guilty on the ground of insanity’.

After nine years in Long Bay Gaol, Dorothy was released and returned to live quietly with her husband . . . But was she really mad, or bad, or neither? And what was the secret that her husband, Harold Mort, kept to his grave?

In an absorbing blend of investigative non-fiction and biography, Suzanne Falkiner delves into the case that has intrigued Sydney for almost one hundred years.

Paperback and e-book | 288pp | AUD$24.99

What they said:

‘Suzanne Falkiner’s Mrs Mort’s Madness is not a cricket book: it is a carefully assembled but highly readable account of a sensational crime. … Nearly a century after it transfixed Sydney, Suzanne has at last rounded the story out.’

— Gideon Haigh

‘…for lovers of true crime, Suzanne Falkiner has written a page turning account of an intriguing case that reads like your favourite crime novel.’

— Meredith Jaffé, THE HOOPLA, 19 December 2014

‘A valuable addition to the genre of true Australian crime writing.’

— Mark Tedeschi QC

‘Lust, murder and deceit are rampant…’

— North Shore Times, 30 January 2015

Mrs Mort’s Madness comes with a skilled writer’s passion for impressive research and digging up a good yarn. [Falkiner] …has the right balance of fact, … history and storytelling enabling the characters to tell their side of the mystery in their own voice. Cricket tragics will no doubt delight in Tozer’s sporting prowess (skilfully introduced in a foreword by Gideon Haigh). Sport trivia buffs will relish the fact that out of 18 murdered first-class cricketers, Tozer was the only one murdered for love. Anyone who enjoyed Falkiner’s historical biography Eugenia: A Man will also enjoy this sizzler.

—Warren Fahey, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 2015

Ultimately, Falkiner does not promote a particular view as to whether Ms Mort was actually ‘mad’ at the time she killed her lover, or just ‘a woman spurned’. However, the options she raises with subtlety and sensitivity are tantalizing, real questions about whether Ms Mort’s homicidal conduct was the result of psychotic illness or premeditatedly murderous behaviour, camouflaged by feigned mental illness. Mrs Mort’s Madness is absorbing reading for a rainy day. It is a fine and accessible piece of historical research that for the most part avoids sensationalism. It reminds us of the complexities of the ways in which women who engage in homicidal conduct are viewed and treated by the criminal justice system. It can be heartily recommended for all with an interest in the history of forensic psychiatry, in women’s madness, and the operation of the criminal justice for those who contend that they were mentally unwell at the time of committing a serious crime.

—Ian Freckelton, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, Volume 22, Issue 2, 2015

True crime stories are gripping, especially when the grisly details of the crime are matched by lashings of romance, passion and tragedy….Suzanne Falkiner combines the conventions of good investigative writing and biography with ‘imaginative reconstruction’ to create a captivating account of this true crime that examines the tragedy behind the headline-grabbing event. The facts of the case are indisputable: Dorothy admitted her guilt immediately, yet she was acquitted on the grounds of insanity and incarcerated indefinitely under the Lunacy Act. Her devastated husband stood by her throughout the ordeal and it was to his home that she returned when released nine years later. With a keen sense of inquiry, Falkiner questions both Dorothy’s madness and its possible causes and she considers alternative interpretations of evidence. She untangles the story’s multiple facets and reweaves them into an absorbing tale of depression, hysteria, social morality, infidelity, fickleness and loyalty set amongst Sydney’s upright middle-classes. Thorough research enables her to draw rich and colourful portrayals of all the characters, mapping their interconnected and claustrophobic social connections and revealing the discreet decadence beneath the respectable social veneer. And in the vein of all good true crime stories, there’s a twist that reveals the most surprising secret of all.

—Kay Donovan, UTS Newsroom

Read an extract...

It was the white cockatoo that had first led them to the murder, they told me. Or was it the mis-delivered parcel?

I had knocked at their door once before, but the small cottage in Lindfield was not immediately willing to give up its secrets. I had no idea who lived there now, and with a change of street name in the intervening years, I was not even certain I had the right address. Beyond a cascade of silver North Shore commuters’ cars flowing homeward on Tryon Road I found some disused-looking stone steps, a rusted gate overgrown with shrubs, and a concrete path winding steeply upwards. I had hesitated at first, unsure of my welcome. Dark blue hydrangeas and drooping palms lent the garden an air of somnolence in the late afternoon, almost of other-worldliness, and so I was not really surprised when the old fashioned electric door bell sounded emptily in the interior and no one responded.

An even narrower path led around the side, but my imagination was already at work and I did not want to be challenged for trespassing. I retreated to my car and made a rough sketch in my notebook: a classic pre-war double-fronted Californian bungalow built on damp-looking sandstone foundations, with a small covered porch and a miniature verandah to the right, its original wooden half-shingles and white-painted timber trim all still intact. Then I walked around by the main road to Owen Street at the back, where my snooping over the fence revealed a more ordinary modern extension and garage. When I lingered too long, a dog began to bark loudly.

When I tried again some weeks later, a teenage girl came to the door and silenced the barking dog to tell me her parents were not at home. I gave her my telephone number. Perhaps they would call me? Research, I said, for a biography. Someone of interest had once lived in the house. I would like to talk to them, and perhaps even to see inside, if they were willing.

Some time later, sitting on a rose chintz sofa in a drawing room pleasantly cluttered with English porcelain and framed family photographs, I told them what I knew. The house had been called ‘Ingelbrae’ in the early part of the last century, I said. I hesitated. Would it disturb them to know that someone had been murdered here, in this very room? The murderer, a Mrs Mort, had shot her doctor as he sat on her sofa writing a prescription. She had been thought to be mad, I added, but I myself was not so sure.

My host, Bruce, a lean man who had introduced himself as a television producer, received the information with equanimity.

‘That would explain the ghost, then,’ he told me.