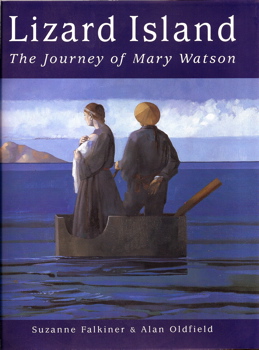

LIZARD ISLAND: THE JOURNEY OF MARY WATSON

LIZARD ISLAND: THE JOURNEY OF MARY WATSON

Allen & Unwin, Sydney 2000

ISBN: 1865085286: a slip-cased collector’s edition of 200, with etching signed by Alan Oldfield $290. ISBN 1865084735: standard hardcover edition, $60

Aboriginal massacres, Australian history, Chinese-Australian history

Available from:www.abebooks.com

WITH ALAN OLDFIELD

93 kilometres northeast of Cooktown lies one of Australia’s most beautiful and secluded resorts—Lizard Island. Mary Watson was 21 years old and had been married less than two years when, in early October 1881, after mainland Aborigines had attacked two workmen at her absent husband’s beche-de-mer station, she set herself adrift in a cut-down ship’s water tank with her baby, Ferrier, and a wounded Chinese servant, Ah Sam. They died of thirst on an island over 60 kilometres away, some eight days after their departure.

At Cooktown it was assumed that Mary Watson had been kidnapped and killed, and when the bodies were found some time later they were returned for a funeral which became Cooktown’s biggest public event, uniting the town in appreciation of her undaunted spirit. Mary Watson, whose diary describing their last days was found with the remains, became an emblem of pioneer heroism for many Queenslanders.

In the meantime, however, a terrible retribution had been visited on the local indigenous people, whom the police were quick to assume had been responsible for the deaths.

Lizard Island was shortlisted for the Queensland Premier’s Literary Awards 2001, Best History Book; and the New South Wales Premier’s History Awards 2002, the Premier’s Community and Regional History Prize.

≈

Prominent Australian painter and teacher

ALAN OLDFIELD was born in Sydney in 1943. After studying at the National Art School in Sydney and travelling in Europe and the USA, from 1974 he lived and worked in Rome for eighteen months on an Australia Council grant. For a year from mid-1988 he was Artist-in-Residence at Linacre College, Oxford. In 1999 he held the same appointment at the Faculty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Cairns. With 23 solo exhibitions and numerous art prizes to his name, including the Sulman Prize and (twice) the Blake Prize for religious art, he also designed sets for the Sydney Dance Company and The Australian Ballet. Until shortly before his death in October 2004 he was an Associate Professor at the College of Fine Arts, the University of New South Wales. Alan Oldfield is represented in the National Gallery of Australia and most state, regional and university collections, as well as in college collections at Oxford and Cambridge and private collections in Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and the United States.

What they said:

Oldfield has taken potent emblems and built them into a visual narrative that traverses the territory of the paradox we have to contend with still. His beche-de-mer pot has the weird resonance of Sidney Nolan’s mask for Ned Kelly. Metal in landscape, Chinese hats in lizard country, salt water and death by thirst.

—Morag Fraser ‘Art History Lessons’ Eureka Street Vol.8 no.7 September 1998

This beautiful book entwines the careful historical work of Suzanne Falkiner with the strong bold paintings of Alan Oldfield, to produce an innovatory account—both detailed and powerful on the one hand, and impressionistic and striking on the other. It demonstrates the capacity of history to move the imagination, to reach out across tragedy, to account for competing and irreconcilable worldviews, and to provide us with an insight into how such violence (including random retribution against the Indigenous people) is rooted in unquestioned beliefs in one’s own cultural superiority.

—Judges’ comments, NSW Premier’s History Awards Shortlist 3 September 2002

Alan Oldfield’s series of paintings, his interpretation of the meaning of Mary Watson’s life and Suzanne Falkiner’s essays is the type of revisionist history that would not meet the approval the Prime Minister John Howard and the historical revisionists that have flourished under his patronage.

…Falkiner examines the material available about the legend of Mary Watson, her four month old baby Ferrier and her two Chinese servants Ah Sam and Ah Leung who were attacked by Aborigines on Lizard Island off Cooktown in 1881. Mary Watson, her baby Ferrier and one of her Chinese servants Ah Sam escaped in a cut down ship’s water tank to a nearby island, dying of thirst while the island birds fluttered around a hidden well. Around 150 Cape York Aborigines were killed in retaliation although none of those shot was involved in the attack on Lizard Island. The bodies of Mary Watson, baby Ferrier and Ah Sam were found among the mangroves of No. 5 Howick Island. Mary Watson left a diary in which she chronicled her last days. The legend of Mary Watson became a metaphor for the European settlers pioneering battle against the wilderness. The legend ignored both the role of the traditional inhabitants and the Chinese workers who were an integral component of the colonisation process of North Queensland. Suzanne Falkiner painstakingly examines the evidence from all sides of the story, undermining the legend with a dose of historical reality. Alan Oldfield through his paintings of the Mary Watson legend attempts to depict the historical reality while imbuing the series ‘with a greater, even cosmic sense of reality’. The paintings, fifteen pieces in all,… are now in the permanent collection of the Cairns Regional Gallery, a few hundred kilometres from where the actual events took place. Lizard Island …dissects a European legend […and] turns the legend on its head providing the social and historical scaffolding that’s required for reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians to become a reality.

—Anarchist Age Weekly Review No.556 21-27, July 2003

Lizard Island neatly balances an historical essay by Falkiner, a study of Oldfield’s life and artistic preoccupations, and numerous full page colour plates. Falkiner’s narrative overview—written in a smooth, taut style that complements Oldfield’s paintings—provides the best account of the Mary Watson incident to date. …footnotes to documentary and official sources sit alongside contemporary Aboriginal oral histories of reprisal massacres. …a bold and imaginative history.

Kate Darian-Smith, Australian Historical Studies Vol.33 No.119 2002

These striking compositions—stark and yet gentle, blue on blue, featuring Aboriginal, Chinaman and white woman—are some of the unforgettable images of Australia, none more so than ‘The Voyage, First Day’ (1992) in which Watson, baby in arms, and Ah Sam standing in the tank look back at Lizard Island , from which they have escaped. The intense and varied blue shading turns re-imagined historical incident towards epiphany. Oldfield’s collaboration with Falkiner has produced a book whose provocations to reflection and further inquiry are as much to be relished as the richness of its verbal and visual narratives.

—Peter Pierce Canberra Times, Saturday 17 March 2001

Read an extract...

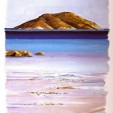

Lizard Island, July 1999

FROM THE AIR, the Great Barrier Reef resembles a giant lapis lazuli flawed with aquamarine and streaks of rusty gold where the coral reefs and atolls break the surface. We fly towards Lizard Island in a fifteen-seat Twin Otter, following the northward path of Captain Cook over the flat blue skin of the world, and as the thousand-mile-long outer reef—graveyard of some 600 wrecks since European discovery—funnels in towards the mainland coast, the pilot passes round a photocopied map outlining in diagrammatic form the labyrinth below. And then the Lizard Group rears up, unmistakable, with its pointers of North and South Direction Islands, its granite peak jutting ruggedly up out of the sea, and we swoop in and land on the ribbon of airstrip that runs parallel to the central valley.

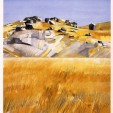

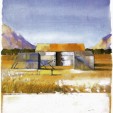

This is a kind of pilgrimage for painter Alan Oldfield. On the afternoon of our arrival we climb the track over Chinaman’s Ridge to where the remnant of Mary Watson’s stone cottage sits squarely on the grassy dune behind the beach at Watson’s Bay. Of a once-sizeable granite blockhouse, now only one corner remains. In front of it stands a Queensland National Parks and Wildlife information board, telling its own version of the Mary Watson story. Beyond is the white, straight beach, littered with small white shells, and towering to the east is the granite backbone of the island: a high, barren ridge that Mary probably once climbed to watch for her husband’s lugger. The tidal creek lined with mangroves runs behind the cottage, and still further back is the pandanus forest that conceals the freshwater spring. It is a tough landscape, made of desiccated dry-land grasses and unyielding rocks; the sun beats down and nothing lies beyond the beach but miles and miles of empty sea.

Later, I sit on a cane chair on the verandah, sipping a glass of chilled white wine, as a giant yellow-flecked monitor lizard struts in slow motion into the vivid green sea cabbage lining the path to the beach, the water appears as a smooth expanse of benign sapphire, all the way to the horizon.

September 9th: Brought the tank ashore as far as possible with this morning tide. Made camp all day under the trees. Blowing very hard. (no water)

September 9th continued: Gave Ferrier a dip in the sea—he is showing symptoms of thirst— and took a dip myself . Ah Sam and self very parched with thirst.

September 10th: Sunday: Ferrier very bad with inflammation, very much alarmed. No fresh water and no more milk but condensed. Self very weak, really would have thought I should have died last night ‘Sunday’.

September 11th: Still all alive. Ferrier very much better this morning. Self feeling very weak. I think it will rain today, clouds very heavy. Wind not quite so high.

No rain. Morning fine weather. Ah Sam gone away to die—have not seen him since 9. Ferrier more cheerful. Self not feeling at [all] well. Have not seen any boat of any description. (No water. Near dead with thirst.)

—Mary Watson’s diary, 1881

‘But the worst part was what happened after. They had a good feast, the people, had a good sleep that night, back at the mainland, taking it easy, mostly they sleep after a feast. There was a big camp of troopers at the Eight Mile, Fraser Island Aborigines, trained to use carbine rifles, and they were like bloodhounds, tracking. These troopers got in a boat round to Flattery Bay, and anchored hidden, out of sight, and sneaked up slow, unseen, and when they saw the smoke of the camp fires they signalled to the white people that the camp was sleeping, and so they were able to move in unawares, and then they shot them, all the women and children alike, while they all were sleeping. All he heard was the echo of guns, and saw people getting up and falling over dying. So most of the tribe was cleaned up. Children and all. But one warrior, Ngamu Wuthur, he got away, maybe one or two others with him, maybe that William Daku too, and he saw the rest lying dead. He was the one that saw his people die at Flattery Bay.

‘Maybe William Daku as a boy, maybe he was on the other side of that camp, when the troopers walked over the hill, when they came to this little beach on this side of the point, came to the same tribe, Yuuru, from the tip of Cape Flattery. But William, he said he could remember the echoes, the ricochets of the bullets in the morning hours, and the women falling down, and the children too. Almost all the tribe. A big slaughter.’

Roy McIvor’s face crumples, as if he is picturing even now the children and women getting up, and then falling, and then not getting up again. His voice falls into silence.