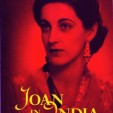

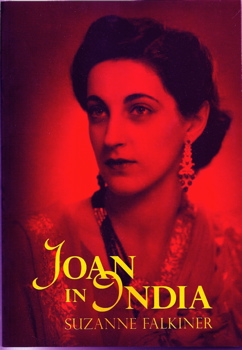

JOAN IN INDIA

JOAN IN INDIA

Australian Scholarly Publishing

November 2008

ISBN: 9781740971621

Australian history, Biography, Indian History

Available from:briobooks.com.au

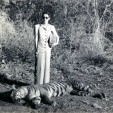

THE FLICKERING, FADED FOOTAGE SHOWS THE RULER OF PALANPUR’S SUMMER HOUSE. ON A TERRACE OVERLOOKING THE LAKE, JOAN TILTS HER HEAD AND TURNS SLIGHTLY, WITH UNCONSCIOUS GRACE. SHE SMILES ENIGMATICALLY. IT APPEARS TO BE A SCENE OF GREAT HAPPINESS,

BUT WHO CAN TELL?

JOAN IN INDIA is now available as an eBook from BRIO BOOKS (with extra photos)

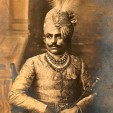

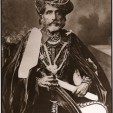

In 1939, young Joan Falkiner’s spirited flight from South Yarra to princely India and her marriage to the Muslim ruler of a small state in Gujarat sent shockwaves through Melbourne society and political reverberations throughout the Raj and—as the kingdoms were about to disappear forever in the maelstrom of Indian Independence—as high as the British throne.

How did it all come about? Through conversations in Melbourne, Mumbai and the South of France, research in the India Office Library in London, and her own observations while travelling in modern India – Suzanne Falkiner traces the course of a most unusual love story.

What they said:

‘The typical fairytale of marrying a prince comes to life in this biography of an Australian girl who leaves her family…to marry a Muslim ruler…in India….Through part travelogue, Falkiner traces the feelings of Joan upon arriving…to wed a man 36 years her senior. Falkiner’s descriptions…are insightful and conjure up the very essence of being on the streets of India. …The documentation of the Independence period…is brilliant and the reader gets a real grasp of how things were at the time. Sure to appeal to serious biography and historical readers, this life history is an extensive portrayal of Joan and the cultural and social implications around her marriage.’

FOUR STARS ****

— BOOKSELLER + PUBLISHER MAGAZINE Melbourne October 2008

‘An impressive writerly achievement. One of the marvelous things about the book is the deft characterization of the interviewees—various Falkiner matrons and matriarchs among them—as well as the wryly humorous self-dramatisation of herself as the biographical detective, quietly displaying the author’s skills as novelist and journalist.’

—Nicholas Jose

‘In her childhood, Suzanne Falkiner heard tales of a cousin called Joan who married a prince from India. As an adult, she decided to find ‘what in actuality might lie in the gap between the happy-ever-after and the faraway kingdom and the real life as it was lived out’….As an historian of India, I can say that Falkiner has uncovered a great deal of information that has never been published, and is not generally known even by scholars working in the field.’

—John McLeod, University of Louisville

‘…both a fascinating narrative of travels around Australia and to India, Britain and France in search of people who knew Joan…and an intimate biography….Suzanne Falkiner was remarkably tenacious in tracking down individuals on three continents who did not provide many clues as to their whereabouts. She embodies the historian as detective who…is not deterred by difficult travelling conditions, unpleasant weather, recalcitrant witnesses or dead ends….Her work is an impressive contribution to the ongoing examination of the role of memory in the writing of the histories of individuals and events.’

—Barbara N. Ramusack, University of Cincinatti

‘Both a passionate romance and a detailed historical novel, Joan in India takes its reader on a captivating journey through an amazing period of Commonwealth history ….Joan’s rebellion against her parents and the restrictions of a conservative 1940s Melbourne society …can be understood by anyone who has survived young adulthood.’

—U, the Magazine of the UTS Community

March 2009

NOW AVAILABLE IN AN INDIAN EDITION FROM YODA PRESS: See NEWS page.

‘While writing about her cousin, Falkiner makes the last few years of the Raj come alive and reverberate. Joan in India is one of those rare books you chance upon that make you glad someone wrote them.’

—Swati Daftuar, THE HINDU TIMES, 3 December 2011

Deftly combining the skills of an archaeologist with those of a historian, Falkiner goes from one corner of the world to another, to excavate the love story of Joan and the Nawab of Palanpur. The breadth is aptly captured in the titles of the different parts comprising the book: Bombay, Palanpur, London, The South of France. …Thus history, romance, and travelogue blend, to add a rich, hard- to-define flavour to the narrative, making it difficult for the reader to lay the book aside until finished.

—Md Rezaul Haque, Transnational Literature, Vol 5, Issue 1, November 2012, Flinders University, Adelaide.

Read an extract...

‘I don’t think Beatrice was quite the type to like having such a lovely daughter’, Lawre remarked, as I made tea for us in her attractive old silver pot tarnished by the sea air and put out on a plate with some paper napkins the pastries I had brought.

‘She liked to be the one who was acquiring all the beaux. She didn’t realise that it was Joan who the Nawab was being attentive to. And this is where I came in, because at about this time I went to India to stay with George Tabuteau, a family friend who was the Director of Medicine in Delhi, and while I was there, Joan was back in Australia keeping up a tremendous correspondence with the Nawab.’

‘But surely, by this time her mother must have known about it?’ I asked.

‘No, she still didn’t.’

‘Beatrice didn’t notice the letters with Indian stamps arriving?’

‘Mmm, yes, but probably she thought he was just being kind to the young thing … Anyway, the first that I really knew about it was when the Nawab invited me to stay at Palanpur on my way home, and of course George Tabuteau would not let me, because in those days you had to have a chaperone. He said it would be no use at all, a young white girl going to stay alone in the Nawab’s establishment; it was absolutely unacceptable. So I got down to Bombay and I was staying with some people my father had horse business with, and all of a sudden, this very nice, smart young aide-de-camp to the Nawab arrived. I had been asked by the Nawab per letter if I would take some things out to Joan and I had said yes, that would be perfectly all right.’

Lawre paused.

‘So you knew?’ I asked.

‘So I knew. Because what I was asked to take out was the most enormous solitaire diamond engagement ring. Luckily, I’d just become engaged myself, and I also had a ring, so I could wear this one as well and there was not going to be any difficulty over customs. I was given various lengths of material and things, presents for me, and asked to take this ring out to Joan with another letter.

‘So I did all this. I duly saw Joan in Melbourne and handed over the ring and the letter. And then Joan was going to be one of my bridesmaids.’

‘Were you in any trouble with Beatrice over this?’

‘Beatrice didn’t really connect me with it at all.’ Lawre smiled in the same rather enigmatic fashion as she had when I had first asked her about Joan’s mother. ‘Beatrice rather regarded me as beneath her notice, I think. Or that was the impression I had.’

I considered this carefully. Had Beatrice decided that she was no competition for her own acknowledgedly lovely daughters? Lawre, at any rate, had few fond memories of her aunt.

‘Anyway, Joan and a friend of hers just snuck off without telling anybody, including me; they just up and left for India. You’d have to look up the newspapers to see who the companion was, it was someone I’d never heard of, another single girl. It was quite daring, really, especially as they left overnight. And everybody was saying things like, “Oh, Joan was supposed to be coming to lunch tomorrow”, and so on.

‘Aunt Beatrice, of course, was furious. As far as I know, they didn’t know anything about it either. There was a tremendous scandal in all the papers.’

‘And so, Joan married almost immediately she arrived in India?’

‘Oh yes. She did’, said Lawre. She glanced at me shrewdly. ‘She would have had to, wouldn’t she?’

Palanpur appeared to have been a peaceful place around 1915, when the building of the new modern Zorawar Palace had begun outside the city walls. Its boundary walls barely reached head height and there was no evidence of any fortifications. The main building, just off a broad, reasonably quiet street, was a pleasing structure rather than an imposing one. Large, rambling and ramshackle, with paint and plaster peeling from its ornate mouldings, it was made up of several extensive wings or pavilions constructed over time and joined by arcades and covered walkways, and surrounded by generous grounds scattered with dry fountains, worn statues and the desiccated remains of formal garden beds. Other buildings behind the main complex might have been servants’ quarters and stables. Still we saw no one around. When we ventured inside, we found a labyrinth of disused rooms littered with dust and pigeon droppings, while crowds of pigeons plummeted through the corridors and the lattice-covered wooden staircases that snaked up the external walls.

Specially imported Afghan artisans had built in painted wood the sections made in the northern style of the Nawab’s Pathan ancestors. In her separate wing the Nawab’s first wife Sukhanbai, a tiny, intelligent woman with bright eyes who spoke only a little English, had remained in purdah, spending her days secluded with female servants and observing the activities of the palace from behind a carved screen.

Now, within the generous sprawl of the whole, signs on the walls indicated that parts of the building were in use as the district court, as well as the collector’s office and police station. Now these various reception rooms, not overly large, in which Joan had once helped to entertain British political officers and visiting princes, had been stripped bare and partitioned into offices, some of which were left casually unlocked, and into which we equally casually intruded. At 7.30 a.m. there still seemed to be no one around. Nearer to 8 a.m., and outside the building again, we saw a bare-chested, middle-aged, moustached man washing himself from a plastic basin on a flat roof-top within the compound. He stared at us with astonishment.

Soon afterwards an adolescent boy dressed in trousers and a singlet began to follow us about and, once he had summoned enough courage to approach, led us to an office where the same moustached officer-now in a crisp khaki uniform-was waiting. He was introduced to us as the Second-in-Command of the Police.

Not knowing what to do with us, and with neither side able to make itself understood, he continued to survey us in silence for a while and then, inspired, summoned another boy who produced a tray of tall glasses of chilled water.

This small ceremony filled up another half-minute or so, and we thanked the officer profusely in English. Then we continued to sit in uncomfortable silence, all of us now dripping with sweat. Our new friend repeatedly wiped his face with a neatly folded handkerchief. Then – once again visited by inspiration – he summoned our guardian-angel-to-be, Mr S. M. Lade.

The problem, Mr Lade confided to us later with just the tiniest of smiles, was that we had inadvertently wandered into the Police Communications Office, an act that – this being a high-security area – should have resulted in our being thrown into jail. All the while we had been drinking our glasses of cold water and trying to think of something to say, it would appear that the Second-in-Command of Police, in the absence of the First-in-Command of Police, had been pondering the pros and cons of arresting us.

That morning Mr S. M. Lade had told us that one of the weathered, vaguely Edwardian-looking statues in front of the main police office was a representation of Joan. There were two statues of female figures standing outside the palace, which seemed to me a rather non-Muslim occurrence in itself. The one on the right had flowing Grecian draperies that could be taken for a sari; the other – with a broken nose – wore an odd, calf-length European-style garment with a laced bodice. The one on the right, Mr Lade was sure, was an Indian woman; the one on the left, he maintained, was Australian. Now that we had arrived, and photographed the statues, and I had claimed to be related to Joan, Mr S. M. Lade was even more convinced. If this were once legend, now it was indubitably true.

When we mentioned to Mr Lade the age difference between the old Nawab and Joan, he looked troubled.

‘Was it a forced marriage?’ he asked.

‘No’, said Coralie, ‘it was a marriage of love’.

Mr Lade was silent. I don’t know if he believed us.

From London I dialled the number in the south of France, and the voice that answered seemed calm and civilised, with a hint of a British accent. It announced that its owner would meet me at Nice airport if I could get on a flight on Friday morning. I would recognise her because she looked, she said, ‘very old’, and her husband would be with her, who looked very English with a little moustache, and a small dog. They had dined in Cannes with Joan the night before, Bee told me, and Joan was pleased I was coming.

The plane was full of rather querulous elderly English couples wearing that odd category of over-colourful clothing called ‘resort wear’ which is seldom seen outside expensive British department stores. They all seemed to know each other. The aisles rang with rarefied British accents as they carefully stacked their wide-brimmed Panama hats in the luggage lockers. As we came in to land over the blue-grey-brown water of the southern coast of France I watched a five-masted yacht ploughing across the Bay of Nice like a toy boat on a pond. All the other yachts were neatly moored in their marinas in rows, with only the odd speedboat furrowing a plume of white like a jet trail in the water. Long ribbons of road followed the attenuated coastline, autoroutes with spaghetti-like entrances and exits, the urban sprawl conjoining what had once been a string of coastal fishing villages into one ugly urban agglomerate, banded to the north by mountains and forest. I had the sensation of looking at a complicated train set spread out on a table, complete with houses like little cardboard boxes, and then suddenly we were on the tarmac. I also had a sense of rising excitement. This sudden resolution to my quest to overcome Joan’s famous reclusiveness had arrived almost too easily. But what would I discover?

Copyright: may not be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without written permission.